In today’s fast-paced world, the importance of carving out time for yourself is often overlooked. Yet, alone time isn’t about loneliness—it’s a powerful tool for self-discovery, rejuvenation, and even strengthening social relationships. This article delves into why alone time is not only vital for personal mental health and creativity but also essential for fostering meaningful social connections. By exploring scientific insights and practical strategies, we reveal how solitude can become the cornerstone of a thriving, healthy social life.

How Alone Time Is Essential to a Healthy Social Life

Understanding the Value of Alone Time for Your Mental Health

Alone time is a cornerstone of self-care and mental well-being. In a culture that often prizes constant connectivity, stepping away from social interactions allows you to reflect, reset, and re-energize. When you take time to be by yourself, you create a space to process your emotions, reduce stress, and cultivate a deeper understanding of who you are. According to Mayo Clinic, periods of solitude can lead to decreased anxiety and improved emotional regulation, as they allow the brain to recover from the overstimulation of everyday life.

Scientific studies have shown that regularly engaging in solo activities can contribute to reduced stress levels, improved concentration, and enhanced problem-solving skills. In essence, alone time serves as a mental reset, promoting overall mental health and wellness. This is particularly relevant in a time when issues such as social anxiety and burnout are on the rise.

Embracing Self-Care: The Role of Solitude in Enhancing Well-Being

Self-care isn’t just about bubble baths and spa days—it also includes the mental space to unwind and process life’s challenges. Solitude allows you to engage in mindfulness practices and reflective thinking, both of which have been linked to improved mental health outcomes. Many experts argue that investing in alone time is a form of self-care that leads to a healthier lifestyle.

Mindfulness meditation, for example, is a popular practice that can be more effective when done in solitude. As highlighted by Psychology Today, regular mindfulness exercises not only reduce stress but also enhance focus and creativity. By integrating moments of quiet reflection into your routine, you cultivate a strong foundation of inner peace that supports both personal growth and your ability to interact with others effectively.

Boosting Creativity and Productivity Through Alone Time

When you give yourself permission to be alone, you also unlock a wellspring of creativity and innovation. Many successful entrepreneurs and creative professionals attribute their breakthroughs to periods of solitude. Alone time removes the noise of everyday distractions, allowing you to focus deeply on your work, explore new ideas, and develop innovative solutions.

Research from Harvard Business Review suggests that a quiet, distraction-free environment can significantly enhance creative thinking and productivity. By setting aside regular intervals of alone time, you can tap into your inner creativity and bring a fresh perspective to your projects—whether at work or in your personal endeavors. This approach not only supports personal development but also positions you to contribute more effectively in social and professional settings.

Balancing Social Interactions and Personal Solitude

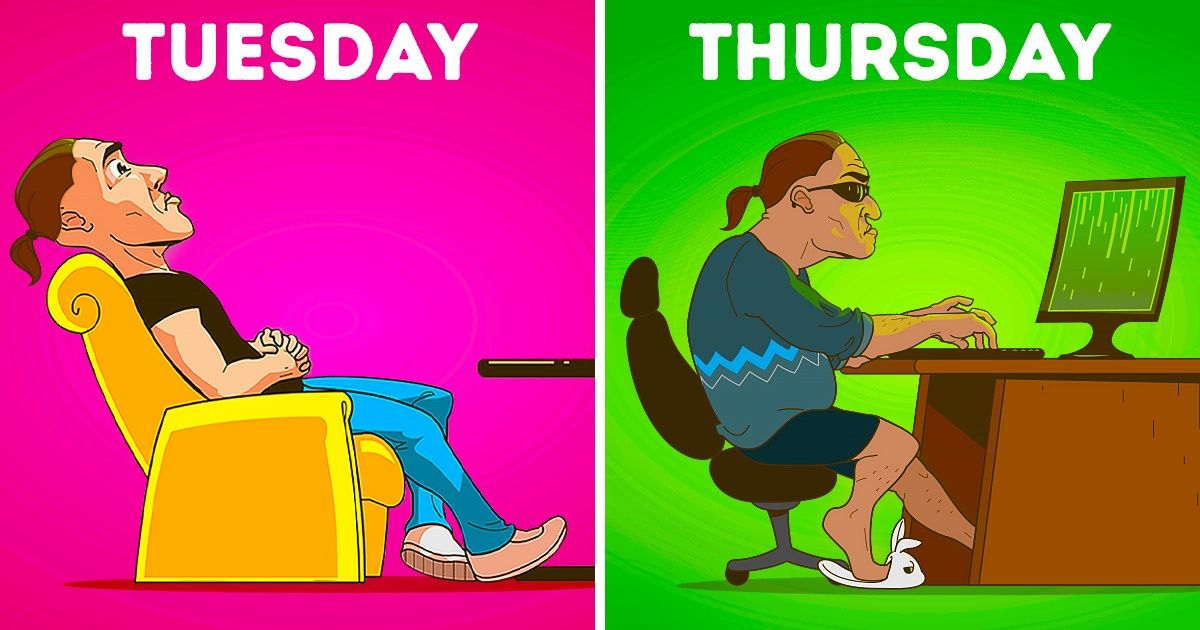

While alone time is crucial, maintaining a balance with social interactions is equally important. The key is to view solitude and socializing as complementary rather than mutually exclusive. Alone time provides the mental clarity and emotional resilience needed to engage in healthy social interactions. When you spend time with others, you bring a more grounded, authentic self to the table.

Experts in social psychology emphasize that quality social interactions can be enhanced by prior periods of reflection. By taking time for yourself, you not only reduce the likelihood of burnout but also improve your ability to connect on a deeper level during social engagements. For those who experience social anxiety, structured alone time can be an essential strategy to build the confidence needed for social interactions.

Practical Strategies to Incorporate Alone Time into Your Routine

Finding time for solitude in a busy schedule can be challenging, but it’s a worthwhile investment in your long-term mental health and social well-being. Here are some practical tips to incorporate alone time into your daily routine:

- Schedule Regular “Me-Time”: Treat alone time as an appointment that cannot be missed. Whether it’s 15 minutes in the morning or an hour before bed, commit to this routine.

- Create a Dedicated Space: Set up a quiet corner in your home where you can relax, meditate, or simply be. A designated area helps signal to your mind that it’s time to unwind.

- Engage in Reflective Journaling: Writing down your thoughts and feelings can be a powerful way to process your emotions. Journaling helps you understand your experiences and fosters personal growth.

- Practice Mindfulness and Meditation: Incorporate mindfulness exercises into your routine to enhance focus and reduce stress. Apps like Headspace or Calm can provide guided sessions.

- Take Digital Detox Breaks: Set aside time to disconnect from digital devices. This not only reduces screen time but also allows you to fully engage with your inner self.

- Mix Solo Activities with Social Goals: Plan activities that can be done alone but also support your social life. For example, reading a book at a local café or taking a solo walk in a park where you might bump into neighbors can be both fulfilling and social.

These strategies not only maximize the benefits of alone time but also ensure that you remain engaged and connected with the world around you.

Alone Time as a Digital Detox: Stress Management and Mindfulness

In the age of smartphones and constant connectivity, digital overload is a major source of stress. Integrating alone time as part of a digital detox strategy can help manage stress and promote mindfulness. Reducing screen time allows your brain to relax and recover from the barrage of notifications and digital distractions.

A recent article on WebMD explains how stepping away from technology can help lower stress levels and improve overall mental clarity. When you disconnect from digital devices, you create a mental space free from external pressures and information overload. This not only supports mindfulness practices but also enhances your ability to engage in meaningful conversations when you do interact socially.

By prioritizing digital detox periods, you give yourself the opportunity to recharge mentally, leading to improved focus, enhanced creativity, and a better balance between personal and social life.

The Science Behind Solitude: Research Insights and Expert Opinions

Numerous studies have confirmed that periods of solitude contribute positively to both mental and physical health. Researchers have found that spending time alone can lead to reduced cortisol levels—the hormone associated with stress—and increased activity in brain regions responsible for introspection and self-reflection.

For instance, research highlighted by the American Psychological Association indicates that a balanced mix of social interaction and alone time can enhance cognitive function and emotional resilience. These findings reinforce the notion that alone time is not an indication of social isolation but rather a necessary component of a balanced lifestyle that fosters personal development and improved social skills.

Experts also note that quality alone time can facilitate deeper self-awareness, which is crucial for forming authentic relationships. When you understand yourself better, you’re more likely to express your needs and boundaries clearly, leading to healthier and more fulfilling social interactions.

Building Stronger Social Connections Through Meaningful Alone Time

While the idea of spending time alone might seem counterintuitive when discussing social life, it is, in fact, a precursor to building stronger, more genuine relationships. When you invest in yourself and take time to recharge, you become more emotionally available and better equipped to nurture your relationships.

Consider the analogy of recharging a smartphone battery. Without periodic recharging, the battery dies, rendering the device useless. Similarly, without moments of solitude, your emotional and mental reserves deplete, making it challenging to engage fully with others. This is especially true for introverts or anyone prone to feeling overwhelmed by constant social interaction.

By striking a balance between personal solitude and social engagement, you foster an environment where your relationships can thrive. Friends, family, and even new acquaintances will appreciate the authenticity and presence you bring to every interaction, as you’re better prepared to listen, empathize, and connect.

Enhancing Your Social Life with Intentional Alone Time

It might sound paradoxical, but intentionally scheduling time alone can actually enrich your social life. Instead of viewing alone time as withdrawal, see it as a deliberate investment in your ability to be present and engaged when you’re with others. This mindset shift transforms the way you interact with your social circles.

Here are some ways intentional alone time can positively impact your social interactions:

- Improved Communication: When you take time to reflect on your thoughts and feelings, you become better at articulating them during conversations. This clarity enhances your communication skills and fosters deeper connections.

- Enhanced Empathy: Spending time alone often leads to increased self-awareness, which in turn allows you to empathize more with others. Understanding your own emotions helps you relate to the experiences of those around you.

- Better Conflict Resolution: Alone time provides the space to process conflicts and misunderstandings. With a calm and clear mind, you are better equipped to address issues constructively and find common ground.

- Strengthened Boundaries: Regular periods of solitude empower you to set healthy boundaries. When you know your limits, you’re more likely to engage in social interactions that respect your needs, thereby creating more balanced and fulfilling relationships.

Integrating Solitude Into Your Long-Term Lifestyle

Adopting a lifestyle that values both alone time and social interaction is a long-term investment in your well-being. It requires a conscious effort to break away from the hustle and bustle of daily life and dedicate moments solely for self-reflection and recharging.

To make this sustainable, consider the following long-term strategies:

- Develop a Routine: Establish a daily or weekly routine that includes dedicated alone time. Over time, this routine will become a natural part of your lifestyle.

- Monitor Your Well-Being: Keep track of your mood and stress levels. Journaling or using wellness apps can help you see how alone time positively influences your mental health.

- Seek Professional Guidance: If you find it challenging to balance social life and personal solitude, consider talking to a therapist or counselor. Professional guidance can provide personalized strategies for managing stress and building healthy relationships. Resources such as BetterHelp or Talkspace can be valuable for those seeking additional support.

- Join Communities Focused on Wellness: Participating in online or in-person communities centered around wellness and self-care can provide additional motivation and ideas for integrating alone time into your lifestyle.

Conclusion: Embrace Alone Time for a Healthier, Happier You

In conclusion, alone time is not a retreat from the world—it is a proactive step towards a healthier social life and personal fulfillment. By investing in moments of solitude, you are not only enhancing your mental health and creativity but also equipping yourself with the resilience needed to form and maintain meaningful social connections.

Alone time allows for introspection, creativity, and a recharging of your emotional batteries. This intentional practice paves the way for improved communication, deeper empathy, and better conflict resolution when you do interact with others. In a world where digital overload and constant connectivity can lead to burnout, embracing periods of solitude is essential for maintaining balance and fostering personal growth.

By integrating the strategies discussed in this article—from mindful digital detoxes to structured self-care routines—you can create a lifestyle that celebrates both introspection and connection. Remember, the quality of your social life is directly linked to how well you know and care for yourself. So, take a moment today to enjoy some quality alone time, and watch as it transforms your interactions, your creativity, and ultimately, your overall well-being.

For further insights on the benefits of solitude and strategies for mental wellness, consider reading additional resources on Harvard Health Publishing and Psychology Today. These sources offer a wealth of information on mindfulness, stress management, and the importance of self-care in modern life.

Embrace the balance of solitude and social engagement, and experience a more fulfilling, healthy, and socially vibrant life. Your journey to self-discovery and improved well-being starts with a single step—acknowledge the power of alone time and let it guide you to a richer, more connected existence.